As expected, on Tuesday night the Board of County Commissioners voted unanimously to discontinue the Durham-Orange Light Rail Transit project. After a failure of negotiations, this step formally discontinues the project and begins a process to reallocate the funds that had been allocated to the light rail project through an amended Orange County Transit Plan.

That process will involve lengthy conversations with community members and potential partners. A lot of time and effort, and difficult negotiation lie ahead. For me, it’s time to pause and consider what has been lost.

The DOLRT, long in planning, supported an ambitious larger vision. The vision was to connect destinations across the Triangle, to allow greater mobility, and to shape patterns of future growth that lessened auto-dependence, minimized sprawl, and fostered equitable new housing opportunities. It was a plan not for five years but for fifty or more. For Orange County, DOLRT had the potential to attract substantial new economic development that would have provided attractive jobs and boosted the tax base. As a former grad student at UNC, I’m sorry for the lost opportunities to move easily between campuses. In a region that values intellectual pursuit as much as ours, this is a real loss.

Shaping development and expanding mobility

The DOLRT would have served three of the state’s ten largest employers: UNC, UNC Hospitals, and Duke University/Hospitals. This was the key to the project: creating the ability for the combined thousands of employees at both hospital systems to take mass transit to work. Though today the employees commute in from all directions, over time new generations of employees would have made the sensible choice to live in places where they didn’t have to rely on a car.

The line would have served three twenty-four-hour employers: UNC Hospitals, Duke Hospitals, and the VA Hospital. Shift workers of all types–medical residents, midwives, doctors and nurses, cooks, maintenance workers, and janitorial workers could have avoided having to drive at odd hours of the night.

Durham has added over 10,000 jobs in the past decade and is an increasingly popular employment site for Orange County workers. And vice versa: many UNC employees (including young faculty who often can’t afford housing in Chapel Hill) live in Durham. Perhaps members of the same household work at opposite ends of the line.

DOLRT would have greatly expanded the universe of job opportunities. If a forty-five-minute commute is reasonable, then the amount of miles that could be traveled in forty-five minutes is much greater by rail than by bus or car. Jobs that once looked like an impossible commute would become real options.

The desirability of being adjacent to transit would certainly have driven up the price of real estate, but that would not have meant there was no opportunity for affordable housing. For a decade or longer, planners in our region have looked to the ways in which other light rail systems have succeeded in incorporating affordable housing at their station areas–through partnerships with nonprofits, trust funds created by government and private foundations, and strategic planning and zoning.

Here it has to be said that Durham had gotten ahead of Chapel Hill: Several planned affordable housing projects in Durham are near a light-rail station, including a low-income housing tax credit project recently secured by DHIC and Self-Help. In Chapel Hill as well, though, affordable housing was not an afterthought: the need was a critical assumption.

Economic benefits for all of Orange County

The potential for commercial development in the Gateway station area–with its proximity to I-40–was great. Corporations that depend on a well-developed transportation infrastructure are not going to be looking to Orange County now. These are jobs that would have come to the county, and considerable tax revenues that could have helped lessen the burden that residential taxpayers bear. To the argument that this line of thinking is speculative, let’s remember that the time horizon is not years but decades. Eastowne, for example, is owned by a non-taxpaying entity now (UNC), but that may not be the case in fifty years. The combination of light rail and interstate highway would continue to attract corporate attention.

The Hamilton Road station presents redevelopment opportunities at at least three sites: Glenwood Elementary (which the school system has said it would consider selling, if the LRT were built); the one-story SECU (can be reimagined as a first-floor credit union with housing, including affordable housing, in upper floors); and the adjacent strip mall. And let’s not lose sight of the fact that East 54, the Aloft Hotel, and the multistory office building next to the new fire station were all permitted on the hopeful assumption that a light rail station would be adjacent.

The development under construction at Glen Lennox similarly was counting on its proximity to the Hamilton Road station for the success of its office leasing.

New jobs at these new or expanded businesses would have been available for residents throughout Orange County. Over the long period of building out the line alone, hundreds of jobs in construction, engineering, and related fields would be available. Summit Engineering in Hillsborough was poised to gain 70 engineering positions for the construction phase.

The schools!

The fact that students at NCCU, Duke, and UNC will not be able to use the light rail to scoot from one campus to the other to take courses represents a double loss. The three have different strengths, and students would benefit from being able to tap in to courses not offered at their university. And academia thrives on cross-pollination of ideas. I am saddened to think of all the learning and coworking and generation of new ways of thinking that will not be happening because it’s too difficult to move around.

Students from Durham Tech’s Orange County campus could have taken the Amtrak from Hillsborough (the new Hillsborough station being one happy outcome of the Transit plan that is happening) to Durham, then on to any of the three universities. The loss extends to high school student as well, who might have benefitted from ready access to classes and internships.

Research Triangle Park was the visionary idea of the 1950s that solidified the Triangle’s position as a magnet for highly educated professionals, while our area universities have been deepening this intellectual wealth with each passing year. DOLRT could have continued in that tradition by strengthening the ties between our universities, and between universities and communities.

And finally,

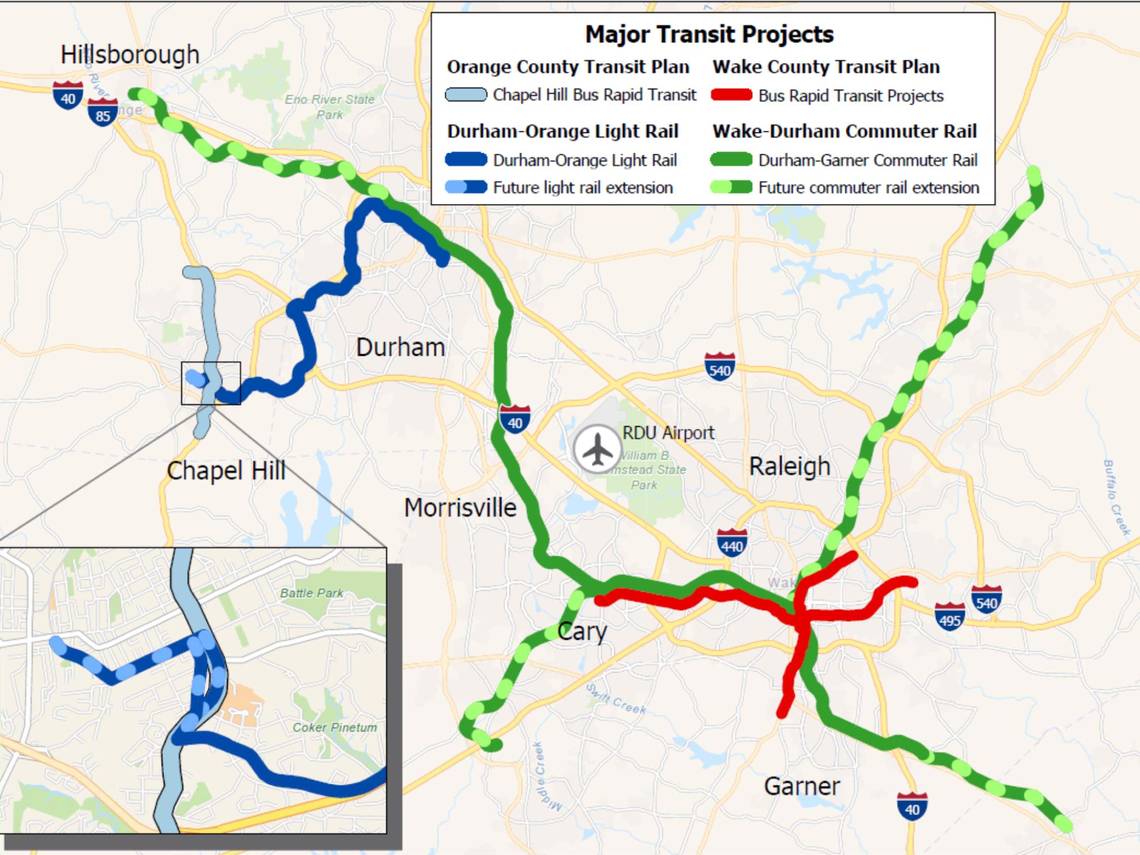

The Orange County Transit Plan, of which DOLRT was a part, provided, and still provides, funding streams for conventional bus service as well as for the planned Chapel Hill bus rapid transit line. Those projects were and remain essential for Orange County. Keeping those plans moving and funded will be critical as we pick up the pieces and go forward with new planning for a regional solution.

Without DOLRT, though, we may be headed for a future in which the major population centers of Orange County are essentially cut off from the rest of the Triangle. We will lose out on the benefits, and we will be failing to share the responsibilities, of being part of a desirable, fast-growing region. Again, much conversation remains ahead of us as we re-imagine what an effective regional transit system can look like. For now, I’m just sorry for what might have been.

Issues: